I treat every InDesign document I make as a challenge. The goal of that challenge is to control everything with styles; if you can make a document with no local formatting, and no manual placement, then anyone can take it away and use it once you’re done. 99% of the time, this isn’t possible — there is almost always something to do after the scaffolding has been erected, some tweak the client needs that just can’t be consistent with everything else, or some design element that InDesign can’t quite achieve without your intervention. But many things are possible because of the vast amount of ways you can combine the options in styles, some of them unexpected.

A title offset into its own column is something you might want to do for subtitles, quote callouts, or any situation where text that is supplementary to the body might be needed. Like many things, it can be achieved in a number of ways, but as you might have guessed we are going to do it with just styles. Up to a certain point, the process is simple — combine complementary indents with a baseline shift — but there’s a trick towards the end that I must credit to the brilliant Michel Allio, alias Obi-wan Kenobi. Have a read of this thread if you want it spoiled for you:

Column for heading, column for body text? – Adobe Forums

If you’d still like me to break it down for you, read on. I’m going to start by presuming you have some text you need to set; mine is something from Project Gutenberg. I’ll also presume you have some knowledge of InDesign.

The first thing we need is body text with a left indent large enough to create space for the titles. Create a paragraph style and give it a useful name; mine will just be ‘Body text’. Apply it to your story and then open up the indents and spacing options.

If you’re following along, set this to 50 mm. If you have your own layout in mind, set to whatever fits. The other settings are just things I added as I went along; they aren’t important for the effect.

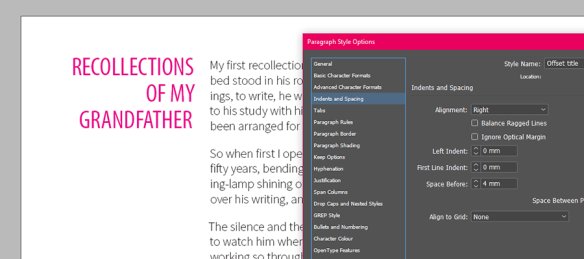

Create another paragraph style for the titles. Mine is called ‘Offset title’, but make it whatever fits your particular schema. Apply it to your titles. Now the real work begins.

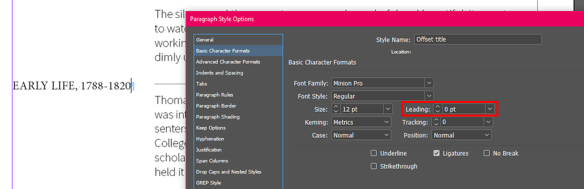

One thing to note at this juncture is that the titles are, and still will be, part of the same story as your body text. They will occupy that space in between the body text paragraphs, even when it appears as if they are sitting alongside them. So, the first thing we need to do is ensure they do not visibly occupy that space, so that they don’t affect the space between body text paragraphs. To do this, they need to have leading set to zero — and, if you used another style as your source for this, ensure they have ‘space after’ set to zero too.

Note that there is still space between body paragraphs here because I have it set that way in the body text paragraph style.

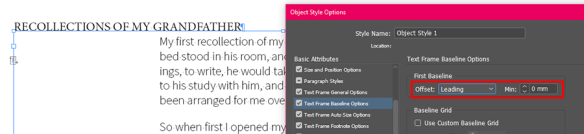

Before we move on, you may or may not notice that there is still space for the title text at the top of your text frame. This is because the ‘first baseline’ setting in the object style for the frame is probably set to ‘ascent’, which means it looks at the ascending characters in the typeface you’re using and sets the baseline as distance from the top of the frame to the bottom of those. We want it set to ‘leading’, which naturally means it is set based on the leading of the paragraph style you’re using. Since that is zero, the baseline sits exactly on the top edge of the text frame.

But the text still appears above the body text, and we want it alongside. For this, we need to apply an appropriate baseline shift to the offset titles paragraph style. If the titles and the body text are the same point size, this shift should look correct if it’s the same as the leading of the body text. The body text has leading set to 15 points. Set this as a negative value in the advanced character formats for the offset titles.

You may well want to increase this value so the top edges of the titles and the body text line up if you increase the size of the title text, but we can worry about that after learning the principles. With no leading and a negative baseline shift, the titles and the first line of body text will now overlap. We will stop this with a large right indent applied to the titles.

With no leading or other spacing, the paragraph just overlaps itself when it breaks lines! Solving this is the trickiest part. To do it, we need to create some new character styles. There needs to be as many character styles for this as there are lines on text in the longest title, less one; I expect my longest title to break into four lines, so I create three styles, named Line 2–4 (omitting line 1 because this will be controlled by the paragraph style alone).

Each of these needs to have a baseline shift applied that is a multiple of that of the paragraph style: Line 2 should have double (30 pts), Line 3 triple (45 pts), and so on.

This is because these character styles are going to imitate leading for us, using line styles. Open up the paragraph style window for the titles again, and go to ‘drop caps and nested styles’. At the bottom you’ll find line styles. Add one using the style ‘none’ and set it to run for one line, then another using the style Line 2, again for one line. Repeat for as many lines as you need.

If you have ‘preview’ ticked, you’ll see the lines arranging themselves as you create each line style.

That’s basically it! Like many complex styles, it’s some work to set up, but of course if you do it right, you won’t have to set it up again. If you want to use larger text in the titles (as is likely), you will need to adjust the baseline shift settings for the title paragraph style and each character style to match. This example uses 24 pt type, and so has a shift of -24 in the paragraph style, and -48, -72, and -96 in the character styles.

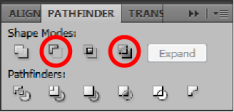

The Pathfinder can also be used to make compound paths. In this case, Minus Front and Exclude would have the same effect as above.

The Pathfinder can also be used to make compound paths. In this case, Minus Front and Exclude would have the same effect as above.